To truly enjoy a Japanese-style meal, it’s essential to understand how it’s meant to be experienced. This article introduces the basic structure and cultural logic behind a typical Japanese meal.

The Structure of a Japanese Meal Set

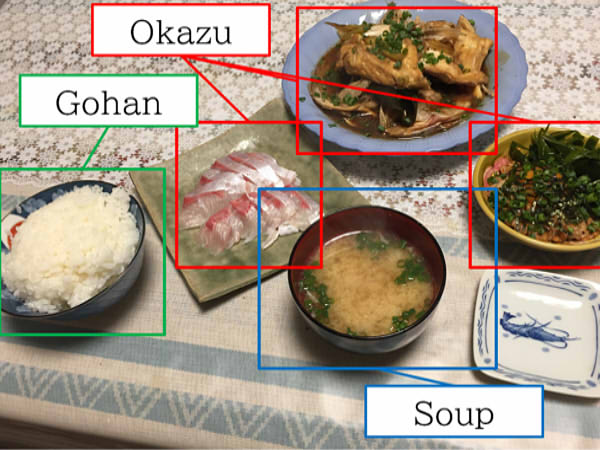

Meal set served in Japan

In everyday Japanese dining, meals are often served as a set called Teishoku (定食). A standard Teishoku typically includes:

- Gohan – white rice

- Okazu – side dishes

- Soup – usually miso soup

Additionally, vegetables are often included to balance nutrition, but the three components above form the core of the meal.

Gohan, Okazu, and Soup: A Cultural Logic

Each component plays a distinct role in how Japanese people perceive a meal. Gohan (white rice) is not just a source of carbohydrates—it’s the heart of the meal. While nutrition labels it as a staple carb, in Japanese culture, rice carries deeper meaning and function.

In a Japanese meal, Gohan is eaten together with Okazu, not separately. Using chopsticks, diners take a small portion of Okazu and rice together into the mouth, creating a harmonious blend of flavors. This combination is not accidental—it’s the expected way to eat.

The Final Cooking Step: In Your Mouth

You could say this is like a final cooking process that happens in your mouth. This cultural nuance is rarely explained to non-Japanese diners, yet it’s crucial. It assumes the diner has grown up with this style and intuitively knows how much rice and Okazu to combine in each bite.

Japanese people naturally gauge the right proportions by looking at the volume of Okazu. The intended way is to finish both the rice and the Okazu at the same time, so each bite is “calculated” from the start.

The “Okawari” System: Second Helpings of Rice

Here’s where it gets interesting. If you’re a big eater, the Okawari system (second helping) comes into play. Okawari usually applies only to Gohan (rice). When expecting a second helping, diners instinctively reduce the amount of Okazu per bite to make it last until the end. Restaurants that cater to this custom often provide enough Okazu and display signs like:

ごはん お替り自由 / Free Gohan Okawari

Typically, younger men are more likely to request Okawari, and restaurants accommodate this with generous portions.

—Japan Traveler Tips—

In many Japanese restaurants, you might see a sign like: ごはん おかわり自由 (Gohan okawari jiyū) – meaning “Free rice refills.”

If you want more rice, you can say: ごはん、おかわりできますか? (Gohan, okawari dekimasu ka?) – “May I have another bowl of rice?”

| English meaning | Japanese | How to pronounce |

| May I have another bowl of rice? | ごはん、おかわりできますか? | Gohan, okawari dekimasu ka? |

| Is rice refill free? | ごはん、おかわり自由ですか? | Gohan, okawari jiyū desu ka? |

| I’d like more rice, please. | ごはん、もう少しいただけますか? | Gohan, mō sukoshi itadakemasu ka? |

| Thank you for the refill! | おかわり、ありがとうございます! | Okawari, arigatō gozaimasu! |

Nutrition vs. Culture

From a Western nutritional perspective, eating more white rice—especially second helpings—might raise concerns about excessive carb intake or blood sugar levels. This is also acknowledged in Japan, but culturally, people are less worried. I’ll explain why in the next article.

Final Thoughts

Understanding this logic is essential if you want to truly enjoy Japanese-style meals. It directly affects how the food tastes and how satisfying the experience feels. For first-timers, the unfamiliarity may lead to a slightly reduced sense of satisfaction—but once you get used to it, this meal culture offers a surprisingly healthy and balanced way of eating.

Let’s dive into the next article!

← Home |

Leave a Reply